The Spirituality of Remembering the ’67 Rebellion

The Rev. Canon Dr. William J. Danaher, Jr.

Rector, Christ Church Cranbrook

Canon for Interfaith and Ecumenical Engagement,

The Episcopal Diocese of Michigan

Originally Published by Detroit Free Press,

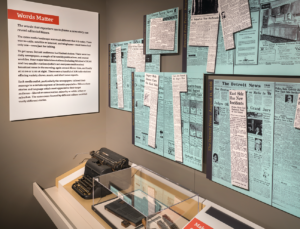

It is humbling to walk through Detroit 67: Perspectives, an exhibit at the Detroit Historical Society. At the start of the careful history presented there, visitors make a stop to create their own headlines. Working with a template and selecting different terms, they can describe the events of 1967 as a “riot,” a “revolution,” an “uprising,” a “rampage,” or a “rebellion.” They can call the people involved “individuals,” “protestors,” “thugs,” “freedom fighters,” or “criminals.” They can characterize the police response as actions that “quelled” or “assaulted” the “gathering” or “gangs” on the streets.

This exercise helps visitors see how the words we use can reveal our biases and attitudes. In an era of “Post-Truth Politics” and “Fake News,” the exhibit invites self-reflection about the history we share, or don’t share, about what happened in Detroit in 1967. The different stories we tell, or don’t tell, are a reminder of what remains for us to learn about each other. The disagreement about language that the exhibit names helps us see the social distance that remains in the greater metropolitan area – distance that is physical, social, and economic.

The tag-line of the Detroit Historical Society is that it is an organization “where the past is present.” Although eloquently stated, the Detroit 67: Perspectives exhibit shows how this phrase represents a complex reality. It points not only to the power dynamics at work in the process of writing history, but in the memories each of us carries in our bodies – whether we personally lived through the events of 1967 or not.

Sociologists have long noted that what binds a community together is the common history and memories people share. In contexts where there has been longstanding injustice and violence, the work of reconciliation stands or falls on developing a shared sense of what happened, and when, and how this past continues to affect the present and future. More than any other accomplishment, the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (1996-1998) did just this in the public hearings it held and in a massive, multivolume report published from 1998-2003.

By revealing the different histories we have learned and the memories we share, Detroit 67: Perspectives shines a light on the work we still need to do in Detroit. In order for us to find wholeness and healing as a wider community, we need to loosen our grip on our own stories and listen to the stories of others. Because there is the deep connection between history and memory – between what is written and learned (history) and the imprint this knowledge makes on our feelings and attitudes (memory).

This is difficult and dangerous work: Memories divide as much as unite. They traumatize as well as heal. They tell truths that are self-evident but largely unspoken. They remind us that the “past” is still “present” within us. Memories haunt us like ghosts or walk alongside us as spiritual companions. They can bind us or set us free.

It is also spiritual work, because what makes a memory “bad” or “good” is not its content, but the way we carry it in our minds and bodies. This is why, in the end, we cannot simply revisit the factual history of the 1967 Rebellion if we want a positive outcome from this commemoration. We need collective reflection, interaction, catharsis, conversation, communion, and conversion if we want to revisit this past in a productive way.

Because this is spiritual work, the interfaith community has stepped forward in two ways. First, working with the Detroit Historical Society, we have organized a weekend of prayer this coming weekend (https://www.detroit1967.org/get-involved/weekend-of-prayer/). At the heart of it is a prayer I was honored to be invited to write:

Loving God,

You alone can give the justice and peace we desire.

You alone can reconcile our past, present, and future.

You alone can give us the grace to walk by faith and to speak the truth with love.

As we remember July 1967, help us build a better July 2017 in our cities and suburbs.

Help us to remember the past faithfully, so that we can live fully in the present and prepare for your future.

Give us your courage and compassion so that we might bear witness to you.

Give us your wisdom and understanding so that we might walk together.

Give us your love, which embraces all and turns no one away.

These things we ask so the world can see and know

that those who were being cast down are being raised up,

that things which had grown old are being made new,

and that your whole creation is being brought to perfection,

by the same God who said, “Let there be Light!”

Amen.

Second, we need to make from our past a kind of ritual that will help us come together in a new, powerful way. Rituals are critical, because – at their best – they help our bodies metabolize our memories in new and powerful ways.

To do this, my collaborator, Oren Goldenberg, and I have worked with the Charles Wright Museum of African American History (https://thewright.org/) to produce a performance art project, People of the Infinite Fires (http://www.peopleoftheinfinitefires.com/). Beginning and ending on the same dates of the Rebellion, this project will create space for ritual catharsis and artistic performance around a sacred fire that will burn continuously for five days.

The fire will be kindled at the Museum’s entrance, on an altar fabricated by Ryan C. Doyle and decorated by Olayami Dabls of Detroit’s African Bead Museum (http://www.mbad.org/). Curated performances by local artists will take place alongside other rituals or remembrances provided by participating community members.

Although the history of the 1967 Rebellion remembers fire as destructive force, fires are also used in many communities to enter sacred space, to purify people, to convey an offering, to hold collective space, and to communicate a divine presence. By ritually keeping a fire, attended by trained fire safety monitors and volunteer fire-keepers, the project will transfigure the way we remember the role fire, and ritual, plays in our lives and memories.

At the end of the five-day period, the fire will be extinguished ceremoniously with water from the Detroit River. The ashes will give nutrients to a seed buried under the fire’s ashes at the beginning of the performance. As the 50th anniversary of the Rebellion passes, the seed will be a ritual reminder of what has taken place, a hopeful promise for the future.

This project seeks to breathe new life into Detroit’s motto as we revisit 1967: “We hope for better things; it will arise from the ashes” (Speramus meliora; resurget cineribus). This motto does not bear the false promise of a world without fire, but rather conveys the hope that fires can be part of a slow and sacred process of social healing and reconciliation. May this hope be fulfilled, God willing.