Words, Truly, Matter.

Matthew J. Schmitt

Co-Founder of The Table Setters and

Compiler and Author the blog Dismantling Whiteousness

Originally Published at Dismantling Whiteousness

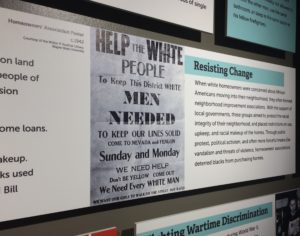

Take a look at these words of this advertisement in #Detroit from 1942: Help the White People To keep this district WHITE. MEN NEEDED to KEEP OUR LINES SOLID. Come to Nevada and Fenlon Sunday and Monday. WE NEED HELP. Don’t be YELLOW, come out. We Need Every WHITE MAN. We want our girls to walk on the street, not raped.

Let those words sink in. What does it conjure up in your mind? I am particularly disturbed by the end lines (beyond the grammatical error), first digging in the “cowardice color” that was also slapped on Asian-Americans, but the notion that if we don’t hold our lines, that our little girls would be certainly raped by non-white people is fear mongering at it’s finest. It has informed our impressions of black men, it has informed the way we police, it has informed the dominant narrative of America: black men are out to get us white folks on every level. This is deeply rooted. And these were commonplace words back then, so it should not be a huge surprise to realize that the original covenants of the suburbs of Detroit very directly did not allow any person with brown skin to purchase or move into homes north of 8 mile. That was the law.

Let those words sink in. What does it conjure up in your mind? I am particularly disturbed by the end lines (beyond the grammatical error), first digging in the “cowardice color” that was also slapped on Asian-Americans, but the notion that if we don’t hold our lines, that our little girls would be certainly raped by non-white people is fear mongering at it’s finest. It has informed our impressions of black men, it has informed the way we police, it has informed the dominant narrative of America: black men are out to get us white folks on every level. This is deeply rooted. And these were commonplace words back then, so it should not be a huge surprise to realize that the original covenants of the suburbs of Detroit very directly did not allow any person with brown skin to purchase or move into homes north of 8 mile. That was the law.

Some laws are meant to be challenged, and I believe we have a moral obligation to break unjust laws when they further oppress people who are already all too used to oppression….

Today, Darcie, Ruby and I had the distinct pleasure of visiting the Detroit Historical Museum’s revealing of their retrospective on the unrest that occurred in Detroit 50 years ago next month. I was most touched by the opening framework of how much words matter, how it included an interactive display where guests could alter the words of a news report. You could describe the event as a “riot,” an “uprising,” a “rebellion;” and you could frame the crowds as “demonstrators,” “troublemakers,” “looters”… Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie teaches us that the story of our country, when told from the point of view of native people’s, would change the “white settlers” into “invaders.” How you describe the events that took place in 1967 here in our city will probably indicate what neighborhood you come from than you may realize. Have you ever spent time hearing about 1967 from the eyes of people who were living in Detroit? Have you ever spent time hearing about 1967 from people whose stores were destroyed? Have you ever listened to the deep anger of people who’ve been told, time and time again, that the bank would not loan them money to fix their roof because the repairs alone would cost more than their house, south of 8 mile, was worth? This exhibit gives you an opportunity to start having those conversations with other visitors as well.

I’ve been contemplating word choice quite a bit lately, particularly as it relates to the role of parents in their children’s education. I’ve heard, so often, “the trouble with these kids’ learning is that the parents just don’t care.” I heard that in New Orleans, and I’m hearing that here about Detroit Public Schools. Just. Don’t. Care. It’s not accurate, and it’s framed in a negative hopelessness. What I learned, both in New Orleans and from our neighbors here in Detroit, is a much more complicated expression of what care means. I am a parent who has the ability to be flexible with my schedule. That allows me to show up for events at school, parent-teacher conferences, meetings with other parents. Many of the parents of the students I taught had been working at the new Wal-Mart in New Orleans East. Wal-Mart is notorious for problems with time-off, and many parents told me their managers threatened to fire them if they even asked for 2 hours to attend a school function. The problem may be that, in a society that begrudges progress towards living wages, parents are not available to be as involved in their kids’ education, which we know plays a huge role. But saying that they “don’t care,” is a word choice that has a damaging rippling effect. Imagine you are working two minimum wage jobs to express care for your family, because unemployment will not feed them, and your child hears a teacher or another parent talk about how parents who aren’t involved “don’t care.” Would your child start to question how much you love them? Would that impact how they respond to you at home? That is a much harder narrative to work with, sure, but in my experience much closer to reality.

So, now, being at a school that is racially and socio-economically diverse, here in a city with a very painful story of injustice and anger boiling over, I am on guard. I have heard statements made by otherwise well-meaning white people that have an edge of condemnation and judgment. I have heard statements made about people on the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum that they don’t know how to prepare their kids properly for school. Words can build up, or words can tear down. Words can set the tone for how whole groups of people are understood.

What kinds of words do you use to describe people who are different than you, and why? What kind of words do you use to describe people you don’t agree with, and why? What kinds of ways do you think your grasp of reality is sound, while another’s is off base, and why?

I have found that learning to listen, and listen again, to people who have experienced less privilege than myself gives me a more balanced view of reality. And that takes time, and that takes effort, but those of us who have the privilege to find flexibility in our schedule, finding space to do things we choose to do, ought to reach out more and more to those people who live daily lives of what they have to do to get by.

There is never any guarantee that you will find compassion and understanding for those who’ve had to live with less freedom than yourself. But I know this: if you never try, if you never sit at a table with someone and ask questions that seek to understand and not judge, you never will. The words you use to describe the people on the other side of the tracks, the people who have a different faith tradition than you, the people who voted differently than you, the people you pass by everyday when you drive across town, those words will remain static and, most likely, lifelessly negative.

Suburban Detroiters: go see this exhibit. It’s free. Listen, talk to other people who are there. Imagine why it’s important to consider a new perspective on racial justice, on systemically unfair practices and policies in our city, on a design that was made to hurt people with brown skin. Imagine what it’s like to be always blamed for your city’s explosions. Consider the immensity of what led to this boiling over: it is not that black people are inherently more dangerous. Remember that the British once referred to American revolutionaries as rioters and looters, too (and the Natives called them invaders). White people, we are not the moral standard by any stretch of the imagination. We’ve just controlled the framing of the story, and the words, for far too long. It’s time to listen and reach out, more and more.

they’re either poison or fruit—you choose.

Choose your words wisely, and I would say, if you are accustomed to framing some people in negative terms all the time, that might be the first group of people you ought to listen to….

Peace by peace,